In October 2013 I wrote about “Valuing Xero in one hour“, and (although it had a bug) came up with a forecast that justified the then $2.2 billion valuation of Xero with a Weighted Average Cost of Capital of 18%.

That forecast was, necessarily, very basic, and the exercise was intended to show how SaaS company valuations are driven by revenue growth.

Xero’s annualised recurring revenue at the time was $70.6 million, while the last 12 months revenue was $53 million. How times have moved on – the recurring revenue is now $638 million and last 12 months revenue $552 million.

The 2013 forecast was over-optimistic with revenue rising to $1.6 billion by March 2019.

While the difference between $639 million and $1.6 billion is a lot – this was off a base of $53 million, so most of the expected growth did occur, just late. (Think about the parable of the expanding lily in the pool). Basically the model was 1.5 years early, and the cause was that the model didn’t reduce the growth rates quickly enough.

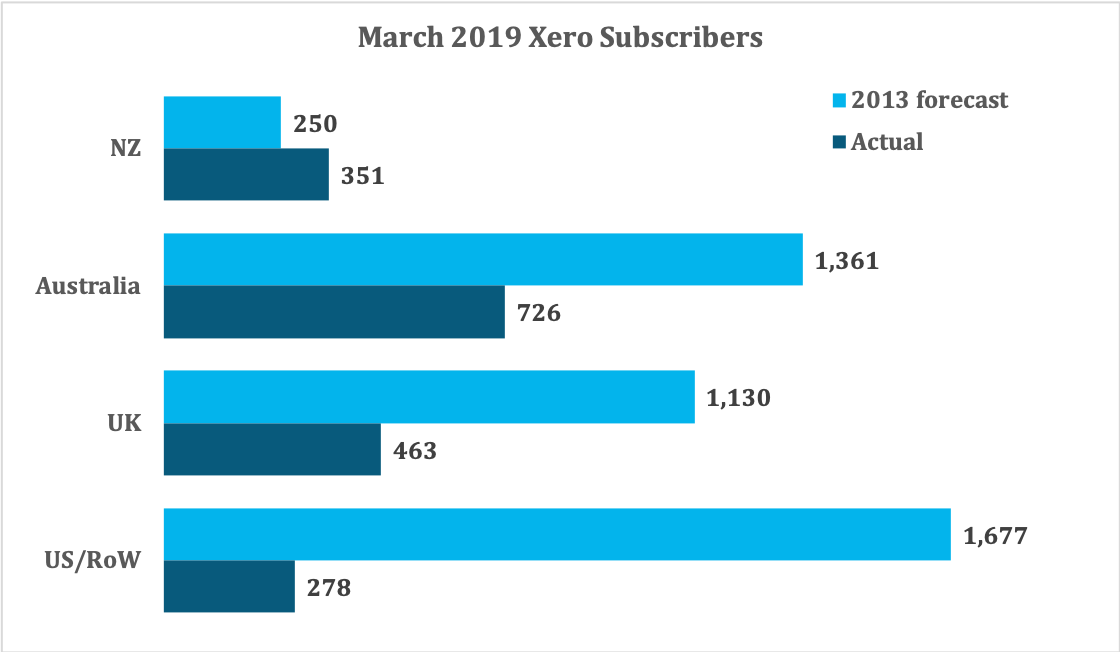

The forecast success varied by country though, with the the growth of New Zealand subscribers and revenue under-projected, and while progress in USA/Rest of World was dramatically over-projected.

There’s a good story here – two of them in fact.

The first is that there is still plenty of growth to come.

The increased New Zealand growth versus forecast shows that the size of the market here is healthier than I expected, and also that the 2013 penetration of the market was lower than I expected. That means we can readjust expectations for the ultimate size of other markets. Along with that it remains very obvious that Xero’s usability dominance and customer lock-in provides it with ample opportunity to increase prices in New Zealand (then offshore) in the future.

Meanwhile there is still plenty of runway in Australia and UK, where adoption of SaaS accounting software has been slow. And the US/RoW markets are even earlier, and with RoW now at $30m revenue and growing faster than any of the main markets I suspect we will see some long term success there. The US market is very difficult, Intuit and ancient arts for doing accounts still dominate, but their turn will eventually arrive.

The second piece of good news is the current valuation (1pm, Friday 17 May, 2019), which is NZ$9.0 billion, is up at a rate of 28.5% annualised return from the October 2013 number.

That represents a 14.1x enterprise value/recurring revenue multiple, which is very high for a company growing at 36% per year. However let’s dive into this a little to understand why it isn’t completely insane.

Firstly though, here’s what Xero has done over the last eight years – consistently strong growth in recurring revenue.

But the share markets have dithered about Xero’s valuation, despite that sustained performance. At times Xero has been over-valued, while at other times it has more clearly been under-valued.

The valuation exercise in 2013 was aimed at showing that growing SaaS companies can justify high valuations using a DCF approach. The market opinions about SaaS companies do tend to vary over time though, and smart investors obviously look to buy when there is a disconnect.

The valuation today is not inconsistent with Xero’s SaaS peers in the USA, with the BVP Nasdaq Emerging Cloud Index boasting a EV/revenue multiple of 12x until just a few days ago. After the Trump incited USA trade war with China escalated that index declined to 10x. It’s worth noting how little exposure Xero has to those two markets.

The second is that SaaS companies, with their recurring revenue, can have value extracted in a very different way than traditional DCF models assume.

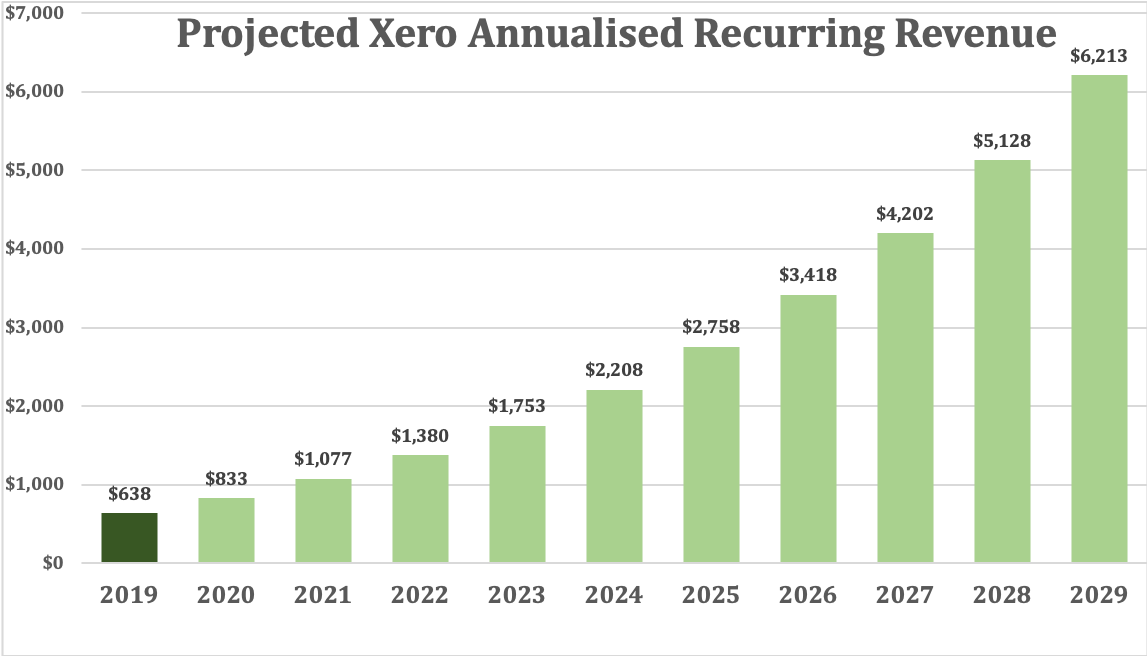

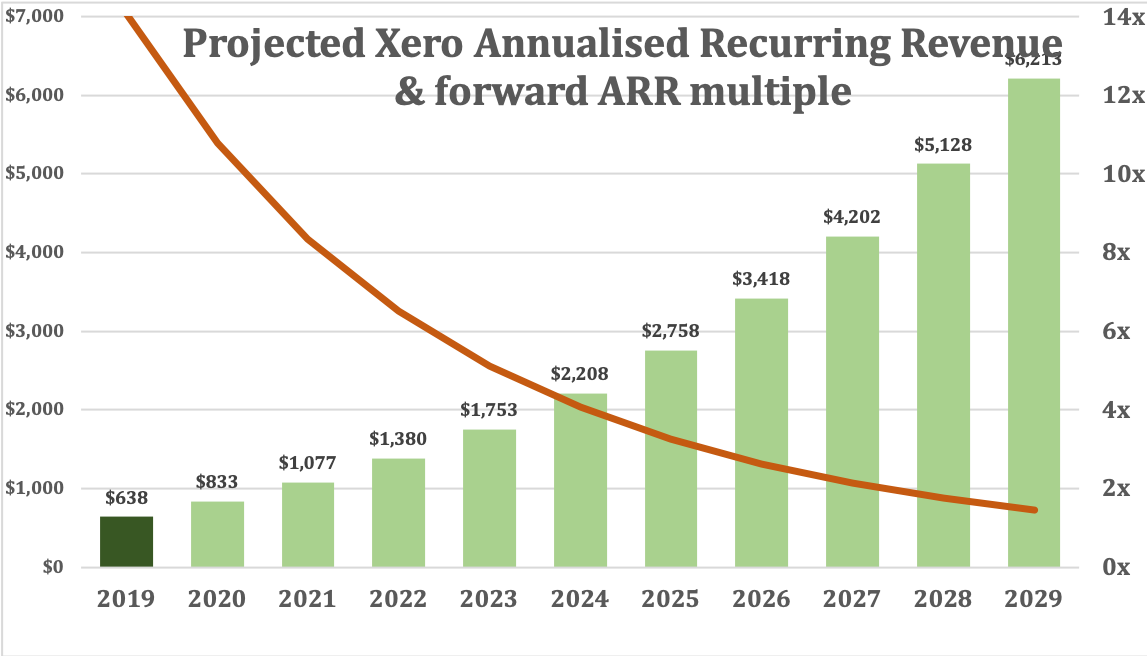

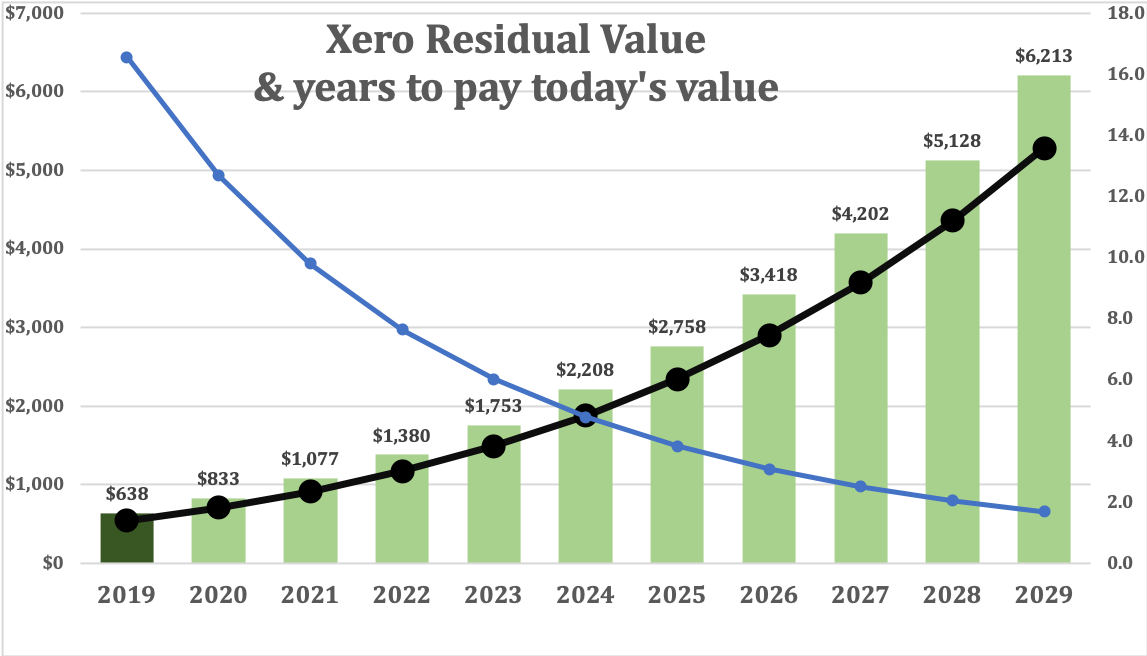

Let’s walk through Xero as an example, starting with a projection of Xero’s annualised recurring revenue for the next few years. This projection deflates the growth each year, so that the 2028-2029 growth is just 21%.

Now let’s add a multiple line – answering what revenue multiple in the future would be required to keep today’s valuation constant?

This shows that if the valuation does not change, and the forecast is correct, then Xero would have a valuation of 3.8x recurring revenue in 2025. Revenue multiples for SaaS companies tend to move in lockstep with the market (and their own growth rate), and that market moves a lot as we saw above. So it’s hard to predict a future stock price, but we can say if Xero’s growth continues then the markets would need to be extraordinarily low for its valuation to be lower than today’s in 2025. And of course there is room for it to be considerably higher.

Revenue multiples for SaaS companies work because a new owner can take out all of the non-essential costs and milk a trailing series of recurring payments. This works particularly well when customers have high switching costs or otherwise have high loyalty to a product, as the case with Xero. If, for example, Xero today decided to abandon growth and focus on delivery only, then, with an 85% gross profit margin, they could generate $542 million of recurring revenue. If that was retained it would take 16.6 years to pay back today’s valuation of $9 billion, a very long time and with high risk.

However if the acquirer instead decided to wait 3 years, then the revenue would be $1.38 billion, the residual recurring profit (after delivery costs) would be $1.17 billion and it would take only 7.7 years to pay back, with plenty of upside beyond that.

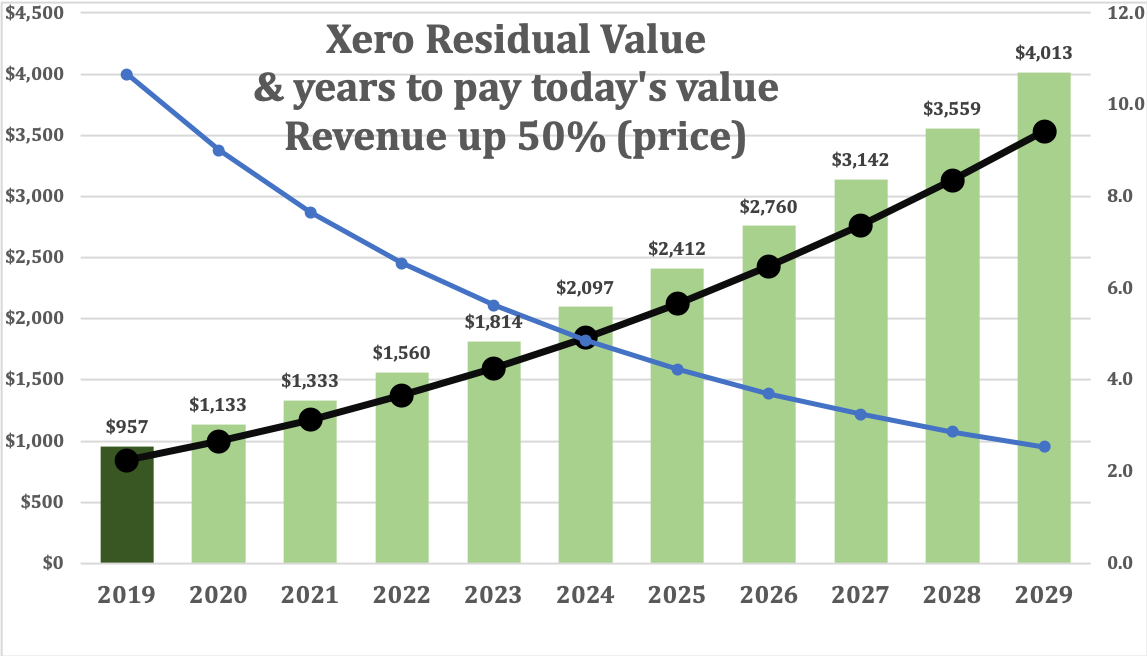

Hold a bit more, and after 6 years Xero would deliver $2.3 billion per year, and the acquirer would be in the black before the end of 4 years. And so on – the chart below shows how the payback period drops over time.

Obviously this is a basic analysis, and the numbers are not that compelling with the current valuation, but for a long term investor Xero is almost certainly going to rise in value. But given what we know about markets it’s just as certainly going to have a rocky ride between now and then.

In reality an acquirer would also change the game by sharply increasing prices, losing a few marginal customers but banking on loyalty and lock in to generate considerable upside, all while reducing costs to serve. They would also continue some growth efforts, lowering the income each year but increasing the net present value.

If increased prices at time of acquisition drive overall revenue up by 50% (stalling growth), then the payback gets a lot nicer. The ARR multiple falls to 9.4x, and the forward numbers look very healthy. The chart below shows that if this happed in 2025 then the acquirer could bank $2.1 billion a year, worth $15 billion at a discount rate of 14%. Any DCF model using realistic discount rates would show the value to investors can easily be justified.